Evaluating OCR systems that convert PDFs or document images into Markdown is far more complex than it appears. Unlike plain text OCR, OCR-to-Markdown requires models to recover content, layout, reading order, and representation choices simultaneously. Today’s benchmarks attempt to score this with a mix of string matching, heuristic alignment, and format-specific rules—but in practice, these approaches routinely misclassify correct outputs as failures.

This post outlines why OCR-to-Markdown evaluation is inherently underspecified, examines common evaluation techniques and their failure modes, highlights concrete issues observed in two widely used benchmarks, and explains why LLM-as-judge is currently the most practical way to evaluate these systems—despite its imperfections .

Why OCR-to-Markdown Is Hard to Evaluate

At its core, OCR-to-Markdown does not have a single correct output.

Multiple outputs can be equally valid:

- Multi-column layouts can be linearized in different reading orders.

- Equations can be represented using LaTeX, Unicode, HTML, or hybrids.

- Headers, footers, watermarks, and marginal text may or may not be considered “content” depending on task intent.

- Spacing, punctuation, and Unicode normalization often differ without affecting meaning.

From a human or downstream-system perspective, these outputs are equivalent. From a benchmark’s perspective, they often are not.

Common Evaluation Techniques and Their Limitations

1. String-Based Metrics (Edit Distance, Exact Match)

Most OCR-to-Markdown benchmarks rely on normalized string comparison or edit distance.

Limitations

- Markdown is treated as a flat character sequence, ignoring structure.

- Minor formatting differences produce large penalties.

- Structurally incorrect outputs can score well if text overlaps.

- Scores correlate poorly with human judgment.

These metrics reward formatting compliance rather than correctness.

2. Order-Sensitive Block Matching

Some benchmarks segment documents into blocks and score ordering and proximity.

Limitations

- Valid alternative reading orders (e.g., multi-column documents) are penalized.

- Small footer or marginal text can break strict ordering constraints.

- Matching heuristics degrade rapidly as layout complexity increases.

Correct content is often marked wrong due to ordering assumptions.

3. Equation Matching via LaTeX Normalization

Math-heavy benchmarks typically expect equations to be rendered as complete LaTeX.

Limitations

- Unicode or partially rendered equations are penalized.

- Equivalent LaTeX expressions using different macros fail to match.

- Mixed LaTeX/Markdown/HTML representations are not handled.

- Rendering-correct equations still fail string-level checks.

This conflates representation choice with mathematical correctness.

4. Format-Specific Assumptions

Benchmarks implicitly encode a preferred output style.

Limitations

- HTML tags (e.g.,

<sub>) cause matching failures. - Unicode symbols (e.g.,

km²) are penalized against LaTeX equivalents. - Spacing and punctuation inconsistencies in ground truth amplify errors.

Models aligned to benchmark formatting outperform more general OCR systems.

Issues Observed in Existing Benchmarks

Benchmark A: olmOCRBench

Manual inspection reveals that several subsets embed implicit content omission rules:

- Headers, footers, and watermarks that are visibly present in documents are explicitly marked as absent in ground truth.

- Models trained to extract all visible text are penalized for being correct.

- These subsets effectively evaluate selective suppression, not OCR quality.

Additionally:

- Math-heavy subsets fail when equations are not fully normalized LaTeX.

- Correct predictions are penalized due to representation differences.

As a result, scores strongly depend on whether a model’s output philosophy matches the benchmark’s hidden assumptions.

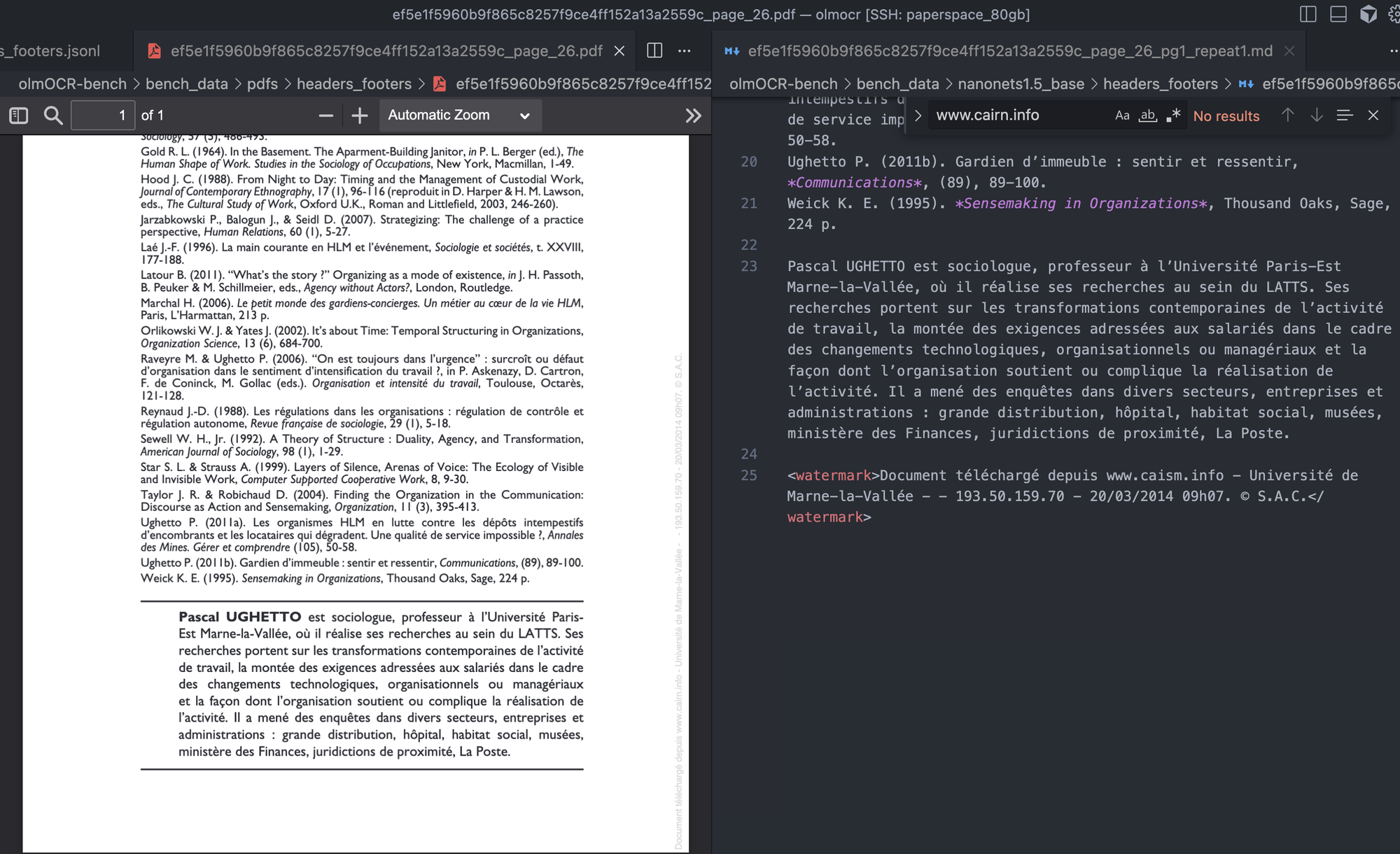

Example 1

For the above image, Nanonets-OCR2 correctly predicts the watermark to the right side of the image, but in the ground truth annotation penalizes the model for predicting it correctly.

{

"pdf": "headers_footers/ef5e1f5960b9f865c8257f9ce4ff152a13a2559c_page_26.pdf",

"page": 1,

"id": "ef5e1f5960b9f865c8257f9ce4ff152a13a2559c_page_26.pdf_manual_01",

"type": "absent",

"text": "Document t\\u00e9l\\u00e9charg\\u00e9 depuis www.cairn.info - Universit\\u00e9 de Marne-la-Vall\\u00e9e - - 193.50.159.70 - 20/03/2014 09h07. \\u00a9 S.A.C.", "case_sensitive": false, "max_diffs": 3, "checked": "verified", "first_n": null, "last_n": null, "url": "<https://hal-enpc.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01183663/file/14-RAC-RecitsDesTempsDHier.pdf>"}

Type absent means that in the prediction data, that text should not be present.

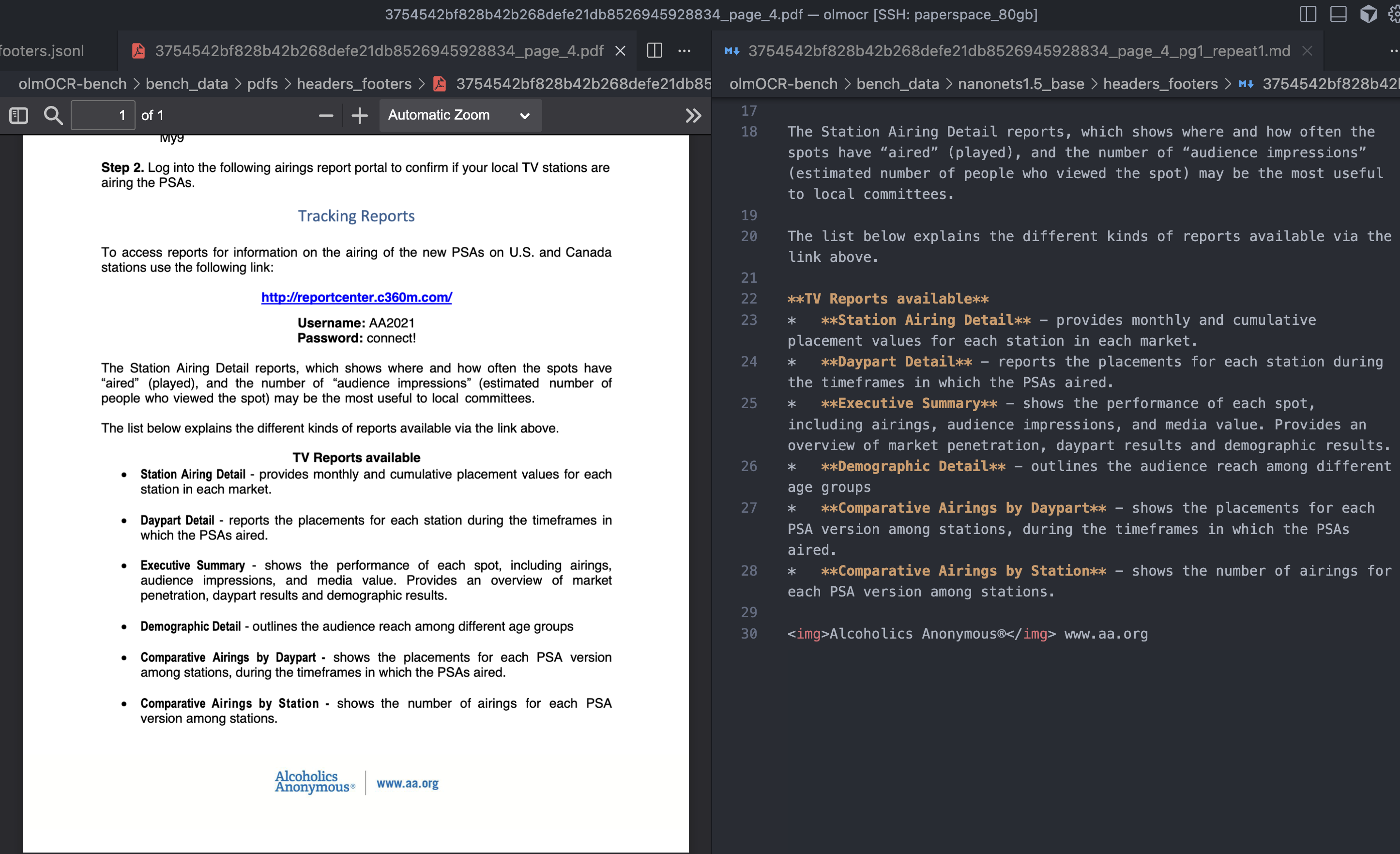

Example 2

The benchmark also does not consider texts that are present in the document footer.

Example in this document, the Alcoholics Anonymous\\u00ae and www.aa.org should not be present in the document according to the ground-truth, which is incorrect

{

"pdf": "headers_footers/3754542bf828b42b268defe21db8526945928834_page_4.pdf",

"page": 1,

"id": "3754542bf828b42b268defe21db8526945928834_page_4_header_00",

"type": "absent",

"max_diffs": 0,

"checked": "verified",

"url": "<https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/literature/PI%20Info%20Packet%20EN.pdf>",

"text": "Alcoholics Anonymous\\u00ae",

"case_sensitive": false, "first_n": null, "last_n": null

}

{

"pdf": "headers_footers/3754542bf828b42b268defe21db8526945928834_page_4.pdf",

"page": 1,

"id": "3754542bf828b42b268defe21db8526945928834_page_4_header_01",

"type": "absent",

"max_diffs": 0,

"checked": "verified",

"url": "<https://www.aa.org/sites/default/files/literature/PI%20Info%20Packet%20EN.pdf>",

"text": "www.aa.org",

"case_sensitive": false, "first_n": null, "last_n": null}

Benchmark B: OmniDocBench

OmniDocBench exhibits similar issues, but more broadly:

- Equation evaluation relies on strict LaTeX string equivalence.

- Semantically identical equations fail due to macro, spacing, or symbol differences.

- Numerous ground-truth annotation errors were observed (missing tokens, malformed math, incorrect spacing).

- Unicode normalization and spacing differences systematically reduce scores.

- Prediction selection heuristics can fail even when the correct answer is fully present.

In many cases, low scores reflect benchmark artifacts, not model errors.

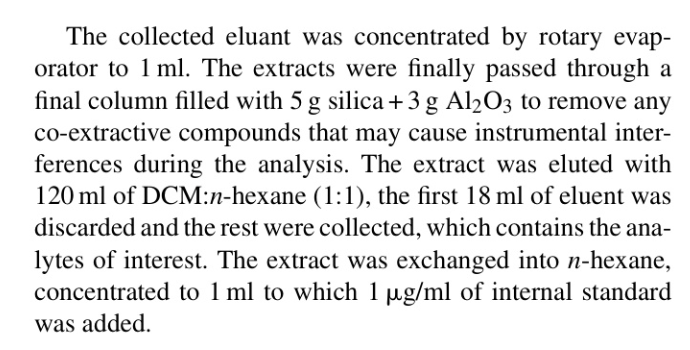

Example 1

In the example above, the Nanonets-OCR2-3B predicts 5 g silica + 3 g Al$_2$O$_3$ but the ground truth expects as $ 5g \\\\mathrm{\\\\ s i l i c a}+3g \\\\mathrm{\\\\ A l}*{2} \\\\mathrm{O*{3}} $ . This flags the model prediction as incorrect, even when both are correct.

Complete Ground Truth and Prediction, and the test case shared below:

'pred': 'The collected eluant was concentrated by rotary evaporator to 1 ml. The extracts were finally passed through a final column filled with 5 g silica + 3 g Al$_2$O$_3$ to remove any co-extractive compounds that may cause instrumental interferences durin the analysis. The extract was eluted with 120 ml of DCM:n-hexane (1:1), the first 18 ml of eluent was discarded and the rest were collected, which contains the analytes of interest. The extract was exchanged into n-hexane, concentrated to 1 ml to which 1 μg/ml of internal standard was added.'

'gt': 'The collected eluant was concentrated by rotary evaporator to 1 ml .The extracts were finally passed through a final column filled with $ 5g \\\\mathrm{\\\\ s i l i c a}+3g \\\\mathrm{\\\\ A l}*{2} \\\\mathrm{O*{3}} $ to remove any co-extractive compounds that may cause instrumental

interferences during the analysis. The extract was eluted with 120 ml of DCM:n-hexane (1:1), the first 18 ml of eluent was discarded and the rest were collected, which contains the analytes of interest. The extract was exchanged into n - hexane, concentrated to 1 ml to which $ \\\\mu\\\\mathrm{g / ml} $ of internal standard was added.'Example 2

We found significantly more incorrect annotations with OmniDocBench

In the ground-truth annotation 1 is missing in 1 ml .

'text': 'The collected eluant was concentrated by rotary evaporator to 1 ml .The extracts were finally passed through a final column filled with $ 5g \\\\mathrm{\\\\ s i l i c a}+3g \\\\mathrm{\\\\ A l}*{2} \\\\mathrm{O*{3}} $ to remove any co-extractive compounds that may cause instrumental interferences during the analysis. The extract was eluted with 120 ml of DCM:n-hexane (1:1), the first 18 ml of eluent was discarded and the rest were collected, which contains the analytes of interest. The extract was exchanged into n - hexane, concentrated to 1 ml to which $ \\\\mu\\\\mathrm{g / ml} $ of internal standard was added.'

Why LLM-as-Judge Is the Least-Bad Option Today

Given these limitations, LLM-as-judge is currently the most practical way to evaluate OCR-to-Markdown systems.

This is not because LLM judges are perfect—but because the problem is fundamentally semantic.

What LLM-as-Judge Handles Well

- Semantic Equivalence Across Representations

LLMs can recognize that:- LaTeX, Unicode, and HTML equations can be equivalent

- Macro-level differences (

A^Tvs\\mathbf{A}^T) do not change meaning - Spacing and normalization differences are irrelevant

- Flexible Reading Order Reasoning

LLMs can assess whether content is complete even when:- Sections are reordered

- Multi-column layouts are linearized differently

- Context-Aware Content Inclusion

LLMs can reason about whether:- Footers, headers, or watermarks should reasonably be included

- Text inside logos or figures counts as content

- Tolerance to Annotation Noise

When ground truth is incomplete or incorrect, LLMs can still judge correctness relative to the document, rather than blindly enforcing flawed annotations.

Why Metric Engineering Doesn’t Scale

Many benchmark failures are addressed by:

- Adding normalization rules

- Expanding equivalence classes

- Introducing heuristic margins

These fixes do not generalize. Every new document type—scientific papers, scanned books, multilingual PDFs, forms—introduces new edge cases. LLMs generalize across these cases without task-specific rule engineering.

Acknowledged Limitations of LLM-as-Judge

LLM-based evaluation has real drawbacks:

- Non-determinism

- Sensitivity to prompt design

- Higher cost and latency

- Reduced reproducibility compared to static scripts

However, these are operational limitations, not conceptual ones. In contrast, string- and rule-based metrics are conceptually misaligned with the task itself.

Final Takeaway

OCR-to-Markdown evaluation is underspecified by nature. Existing benchmarks conflate formatting, representation choices, and semantic correctness—often penalizing models for being correct in ways the benchmark did not anticipate.

Until benchmarks explicitly embrace semantic equivalence, LLM-as-judge remains the closest approximation to human judgment and the most reliable evaluation signal available today. Benchmark scores should therefore be treated as partial indicators, not definitive measures of OCR quality.